remiXML: Incorporating XML in First Year Writing

Background

This project was created for the Digital Humanities graduate certificate at Northeastern University; the project began in 2016 and ended in 2018. I began this project in my first year of my PhD program, collected the data by incorporating the XML schema in the class in my second year, and presented on my findings and reflections later on. This page will go through the process and justification of the project as well as the results from both versions 1 and 2.

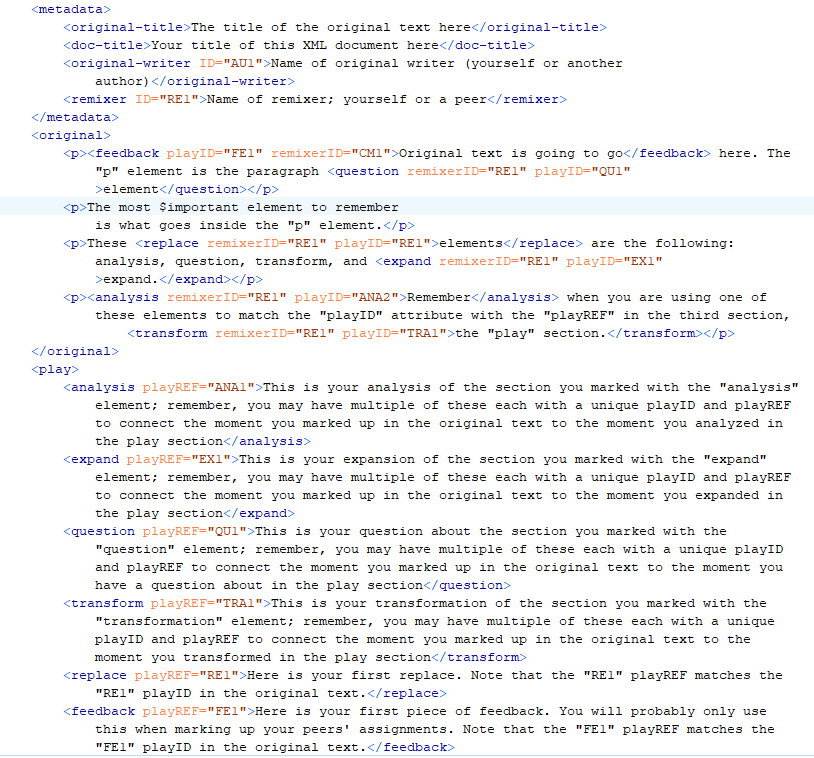

In my First Year Writing course, I have merged my interest in fan studies, critical pedagogy, and DH by building an XML (extensible mark-up language) schema that asks student writers to remix shared readings and their peers’ texts. This schema, called the remiXML, is broken up into three sections: the metadata (descriptions of the file, author, remixer, and title), the original text (either the shared reading or a student writers’ assignment), and the play section (where the student writers create their interventions about the text).

Motivation

Student writers are agents of social change who can begin to recognize and critique the narratives and technologies that have shaped and defined us, so that they may become agents of change across disciplines, communities, and larger institutions.

- How can student writers make direct textual interventions and see the results of these interventions?

- How may these interventions change their views on reading, writing, and whose stories are told?

- How may the inclusion of XML teach students about data modeling, textual analysis, and transformative writing practices?

- How do students articulate the constraints and affordances of the technologies incorporated?

Framework

Critical pedagogy – a teaching ideology coined by Paulo Freire (1968) that centers around justice and activism – has become a central threshold concept in Writing Studies (Adler-Kassner & Wardle, 2015). Researchers have applied and reimagined Freire’s concept of the institution being a biased, non-neutral space that reinforces the oppression of historically marginalized voices. In a classroom facilitated by a critical pedagogue, the space is used to subvert this oppression and to encourage students to claim agency of their learning and position in the institution (Kincheloe, McLaren, Steinberg, & Monzó, 2017). My classroom centers around the idea that the student writers and myself are agents of social change who can begin to recognize and critique the narratives that have shaped and defined us so that we may become agents of change in disciplines, communities, and larger institutions. Because of this central framework in my pedagogy, as the teacher I have committed to transparency (explaining why I have constructed my curriculum, chosen a certain reading, designed an assignment, etc.), active listening practices (during one-on-one meetings and in the classroom), adaption (such as re-shaping the class according to discussions and students’ perspectives and being open about this re-shaping), and intervening (if there are moments when a student writer reinforces, rather than subverts or questions, problematic narratives). I have also asked the student writers in the class to do the same.

Relative to Writing Studies, Digital Humanities is a fairly new field and has begun in the past decade to further expand on critical practices and pedagogy. After the first Debates in the Digital Humanities edited collection was published in 2012 when Stephen Brier asked “where is pedagogy in DH?”, there has been a rise in conversations about incorporating pedagogy into Digital Humanities. In fact, the Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities project has asked researchers who are both compositionists and digital humanists to come together and define major key terms for digital pedagogy (Davis, Gold, Harris, & Sayers, 2017). Although digital pedagogy suggests that using digital tools is one of the main teaching methods, Paul Fyfe (2011) argues that defining digital pedagogy should focus more on the pedagogy, or encouraging our class to recognize how tools shape us and, more importantly, how we shape ourselves by using these tools. These tools are not “simple solutions to social and cultural problems,” but rather add new social and cultural layers, changing how relationships and identities are formed and how meaning is shaped (Davis et. al, 2017). I have brought these ideas into my classroom and asked the student writers in my class to think about them, as well; many of our discussions about XML revolve around why we use it, what its constraints and affordances are, and how we can play with and change what it offers. Because I designed the schema myself, I can practice adaption in the schema design and change it as we move throughout the semester to fit student writers’ uses of the tool and what they wish the tool could offer.

Why XML?

In Trey Conaster’s (2013) conference piece reporting on the progress he has made incorporating XML in his writing class, he argues that XML has “enabling constraints” – using XML “forc[es] composers to describe or make explicit their rhetorical and compositional choices, to define what they’re doing as they’re doing it, the XML editing software renders metacognition, or the reflection on one’s own thought processes, as one and the same with composition, the act of typing words on the computer screen.” For Conaster’s course, the student writers use XML to write their papers and mark up and make explicit the rhetorical choices they made; what Conaster argues that is crucial is that XML “renders metacognition” and the constraints force student writers to “define what they’re doing.” As student writers are composing and marking up their pieces, they have to pay attention that their mark-up is well-formatted. More importantly, however, they have to understand what the elements and attributes each mean and how they can use these to mark up their texts. For example, if there is an element named

The process that Conaster’s schema centers around is the actual composing process. my schema, however, centers around the reading process – to encourage critical and transformative reading practices, other instructors incorporated TEI into their classrooms using the elements to discuss close reading as well as generic forms (Brooks, 2017; Singer, 2013). The remiXML schema design is inspired by the process fans use when approaching the canon texts they love. When fan writers and artists watch, read, or listen to the canon texts they love, they play within the “fault lines within dominant ideology” in order to “build their culture within the gaps and margins of commercially circulating text” (Jenkins, 1992/2014). Fans focus on the alternative, reading the canon texts they love with the intention to transform it. Fans thrive in their communities and, while my classrooms are communities of their own, they are certainly not fan communities. By using fans’ reading process as inspiration, though, the remiXML centers around marking up and annotating an original text. Unlike reading PDF, eBook, or hard-copy, reading in Oxygen means that student writers have the chance to actually edit texts both through mark-up and actually changing the text; for example, student writers can delete sentences and words and entire paragraphs of an original text if they wished, blurring the lines of writer ownership. As the student writers read the original texts, they mark up moments with specific elements; these elements are each designed to revolve around the student writers’ interventions in the text. The student writer then, in the last section of the schema, writes out their interventions. This process also forces student writers to read more slowly; since they have to mark up specific moments then go to the bottom of the schema where they add their interventions, they are forced to read and re-read details of the text. When they finish marking up the text, student writers can use the XSLT stylesheet to transform their XML to an HTML file, which not only highlights the moments when they intervened, but shows their interventions through pop-ups. Most importantly, however, marking up the text with the remiXML schema asks students to work within the elements and intervene in ways that resemble the elements in the schema. Just as the student writers in Conaster’s class begin to compose in ways that fit in with the schema’s constraints, student writers using the remiXML begin to read and imagine interventions in ways that will fit with the schema’s constraints.

The samples below have all been collected from First Year Writing courses. Students signed consent forms to having their work appear in research. Identifying features have all been removed to protect students' privacy. To read the students' different engagements with the text, click on any text that is not black. Each element has its own color. You can also scroll to the bottom of each text to see a summary of the students' transformations with the XML schemas.

Version 1

The first version, which I used in my Fall 2017 semester First Year Writing course, had more generalized elements that did not encourage specific categories. There was also an element, called feedback, which encouraged peer revision techniques. Student writers in the classroom used the remiXML version 1 to mark up published texts by authors like Roxane Gay, Claudia Rankine, and Shirley Jackson. They also used the remiXML to mark up each others’ essays as an attempt to bridge the gap between “professional” writer and themselves. The version was successful in encouraging peer review, but most student writers used the and tag on each others’ work. The focus became more on “review” than “engagement.” To find more documentation about remiXML version 1.0, please visit the version1 folder on my GitHub page. For a breakdown of the schema and explanation of each element and attribute, read the README.

One of the challenges with using the remiXML schema for peer review feedback were the conflicts between the original intention of the schema design and how the students wanted to use it for feedback. Half-way through the semester, students asked for the includion of a "feedback" element. Then, for peer review, students mainly alternated between the "question" and "feedback" element. I also used the remiXML schema to provide feedback and found I, too, was mainly relying on those two elements. The issue here was how the design intention did not mirror the genre of peer review. Peer review relies on audience perspective, while fanfiction genres rely on transformative elements. Both these genres are about audience, but the audience roles differ.

Here are some samples of student work from the first version:

- Remixing "I Was Once Miss America" by Roxane Gay, where the student reflects on how their own experience mirrors Gay's experience.

- Remixing "I Was Once Miss America" by Roxane Gay, where the student reimagined a more "happy" ending in whichh Gay fighting back in school and making friends.

- Remixing "I Was Once Miss America" by Roxane Gay, in which the student digs further into Gay's perspective and point of view as well as transforms it in some moments.

- Peer & instructor review on students' original work, which shows both a student and Cara providing feedback on another students' first draft.

- Peer & instructor review on students' original work, which shows both a student and Cara providing feedback on another students' first draft.

- Peer & instructor review on students' original work, which shows both a student and Cara providing feedback on another students' first draft.

Version 2

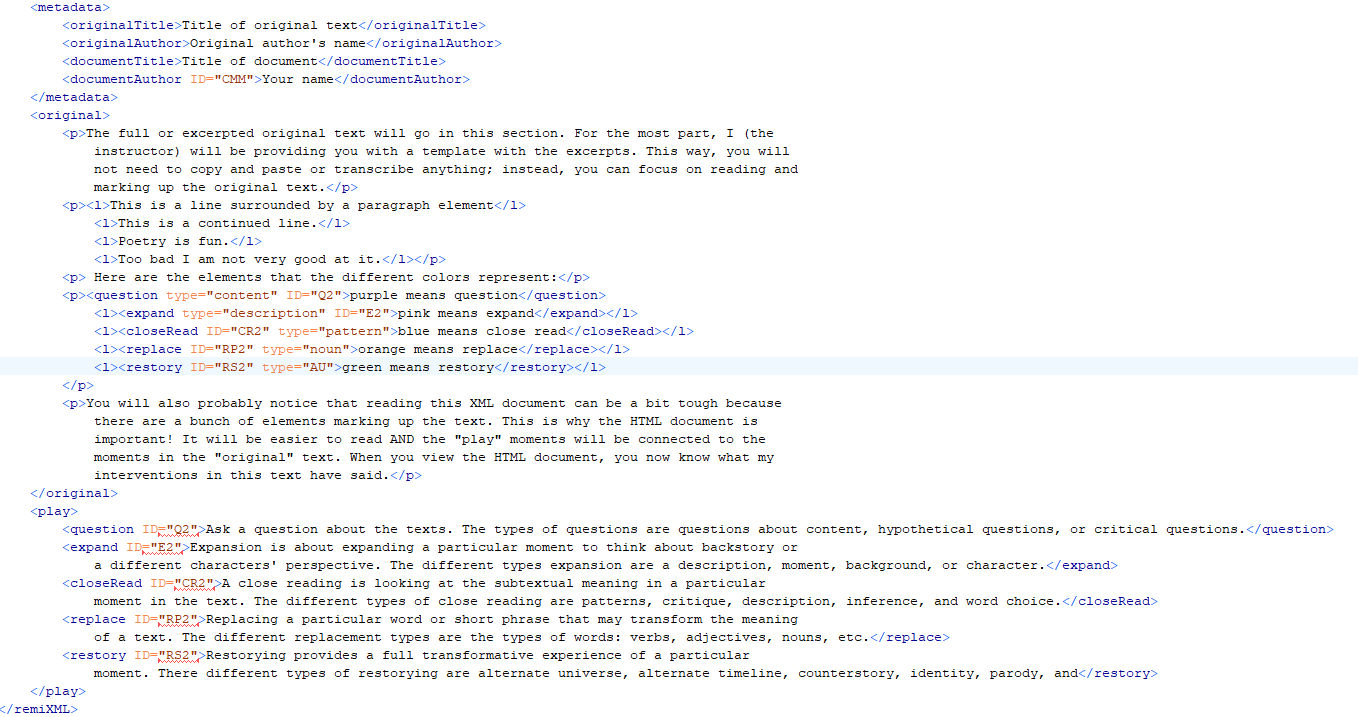

Based off this experience, remiXML version 2.0 focused more on creative approaches to reading and attempting to categorize types of reading more explicitly. For example, the element became and several attributes values were added. Several elements were in the original version (restory was called transform, however); with the extra attributes, though, I have hoped to inspire student writers to use these attributes in more specific and pointed ways (the new attributes were borrowed from Ebony Elizabeth Thomas and Amy Stornaiuolo's article "Restorying the Self"). For example, the element has an attribute value called “bending,” which asks the student user to bend the identity of a particular character. This is inspired by racebending, queerbending, genderbending, and other types of identity bending practices that fanfiction writers take on in their work.

The feedback element was also erased in the second version, as I decided to assign the remiXML for student writers to mark up professional authors’ texts instead of both professional authors’ and their peers’ work. I began referring to “peer review” as “peer engagement,” as well, to encourage a focus on reading as active and excited readers, rather than reading to review. For more documentation about remiXML version 2.0, please visit the version2 folder on my GitHub page. For a breakdown of the schema and explanation of each element and attribute, read the README.

Before I introduced how to use XML to encode a text, I first had them annotate a short story in anyway they desired. Their annotations analyzed and reacted to the texts in fairly traditional ways: they addressed moments they had questions about, related parts of the story to their own experience, and described some of the literary devices being used. While their annotations were substantial, I wanted to encourage them to approach texts with a transformative mindset, understanding the malleability of narratives and storytelling. The remiXML version 2 asked them to encode a text thinking about transformations, specifically "restorying for justice." What and who may be overlooked in narratives? In what ways can we transform a story to think about different perspectives? Using this framework, students encoded different excerpts of texts, both texts I assigned and texts of their own choosing.

Here are some samples of student work transforming piece they were assigned:

- Remixing "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson, which examines the background of characters, traditions, and naming.

- Remixing "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson, which restorys the piece into a more modern setting by replacing small details with more modern technology and fashion.

- Remixing "The Lottery" by Shirley Jackson, which also restorys the piece into a more modern setting, specifically a corporate, capitalistic setting.

- Remixing The Hunger Games by Susan Collins, which restorys and expands upon a particular exchange between Rue and Katniss, drawing more connections as well as demonstrating differences between characters.

- Remixing The Hunger Games by Susan Collins, which focuses on Katiss' pain as she watches Rue pass.

Two of the larger assignments heavily relied on encoding excerpts of texts they chose and then transforming those texts based on their transformation. These are excerpts from the texts students chose to transform, which provide a glimpse into how they decided to transform them:

- Remixing a piece chosen by the student, which takes a children's book and brings in a element of gender inequality and challenging this misogynistic systems.

- Remixing a piece chosen by the student, which transforms a scene from a Gray's Anatomy when a character faces her mother's homophobia; instead, in the students' transformation, the character's mother sees the error of her ways.

- Remixing a piece chosen by the student, which transforms a scene from 1984 to reimagine the Brotherhood as a Sisterhood rebelling against misogyny.

Results & Reflection

- Some students enjoyed it, some did not (based on in-class conversations, one-on-one feedback, evaluations, etc)

- Using the schema for two different genres (peer feedback and transformative interventions) removed the original intention of the schema

- Students enjoyed thinking deeply about representation and whose stories are told/not told (as well as how they are told/not told)

- Basing assignments on students’ XML encodings created a better connection between their reading and writing practices

- If I do this again: have students engage more deeply with the back-end and transformations; discuss coding literacy and rhetorics

Recommendations

Based on work from both versions of the remiXML and both courses, I have come up with some sugestions for either incorporating XML in a writing course or, more broadly, incorporating digial infrastructure in a course that does not center the digital. These findings are based on either challenges we ran into during the two semesters or succesful moments in the semester.

- Repeat, repeat, repeat. Teaching digital platforms requires repetition and the use of a specific vocabulary set as well as a thorough explanation and repetition of the vocabulary (i.e., GitHub’s “push” and “pull”.

- Documentation and resources are key. Similar to constant repetition, providing documentation and explicit instructions that students can follow along with helps as they work with a technology that they may be used to. Creating workflow documents and breaking down exact steps makes it easier for students to follow along, but also provides them with enough information that they are more focused on what the tool can do, rather than how to use it.

- Be transparent: Provide justification! Explicitly explain why particular technologies are used over others. One of the reasons we used XML was because of its constraints that pushed students to read texts from a transformative lens, and one of the reasons we used GitHub was because it's a collaborative platform that can be private. Plus, these technologies allowed us to talk about important digital infrastructure like data modeling, cloud storage, version control, and digital collaboration/workflow.

- Encourage feedback from students. Check-in with students to see what is working and what is not working. Provide space in both class and outside of class for students to ask questions.

- Be comfortable with not knowing. Remind your students that it is okay not to know. You may also do this by talking about your own struggles and journey with the technology.

- Encourage students to be critical of and creative with the tools. Due to the constant conversations in the classroom, student writers have voiced their frustrations with their tools. More importantly, however, they have pointed out where the schema has been useful and where it has not. For example, several student writers have requested some kind of “react” element where they can leave comments that surround their initial affective reactions. Also, two of the student writers used the remiXML to creatively mark-up their own assignment; they used the elements provided to add a meta-layer to their final draft to allow the reader to understand why they made the revisions choices that they made.

References

Adler-Kassner, L., & Wardle, E. A. (Eds.). (2015). Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies (Classroom edition). Logan: Utah State University Press.

Brier, S. (2012). Where’s the Pedagogy? The Role of Teaching and Learning in the Digital Humanities. In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved from http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/8

Brooks, M. (2017). Teaching TEI to undergraduates: A case study in a digital humanities curriculum. College and Undergraduate Libraries, 1–15.

Conaster, T. (2013, February 5). XML in the Writing Class. Retrieved from https://www.hastac.org/blogs/conatser4/2013/02/05/xml-writing-class

Crompton, C., Lane, R. J., & Siemens, R. G. (2016). Doing digital humanities: practice, training, research (1st edition). New York, NY: Routledge.

Davis, R. F., Gold, M. K., Harris, K. D., & Sayers, J. (Eds.). (2017). Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities. New York: Modern Language Association. https://digitalpedagogy.mla.hcommons.org/description/

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed). New York: Continuum.

Fyfe, P. (2011). Digital pedagogy unplugged. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 5(3). Retrieved from http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/3/000106/000106.htmlhttp://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/62

Gold, M. K. (Ed.). (2012). Debates in the Digital Humanities. Minneapolis London: University of Minnesota Press. _________ & Klein, L. F. (Eds.). (2016). Debates in the digital humanities: 2016. Minneapolis London: University of Minnesota Press.

Jenkins, H. (2014). Textual Poachers. In K. Hellekson & K. Busse (Eds.), The Fan Fiction Studies Reader (pp. 26-43). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. (Original work published 1992)

Kincheloe, J. L., McLaren, P., Steinberg, S. R., & Monzó, L. D. (2017). Critical pedagogy and qualitative research: Advancing the bricolage. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th edition). Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne: SAGE.Singer, K. (2013). Digital Close Reading: TEI for Teaching Poetic Vocabularies. The Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, 3. Retrieved from https://jitp.commons.gc.cuny.edu/digital-close-reading-tei-for-teaching-poetic-vocabularies/

Stedman, K. D. (2012). Remix literacy and fan compositions Computers and Composition, 2, 107-123. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2012.02.2002

Thomas, E. E., & Stornaiuolo, A. (2016). Restorying the Self: Bending Toward Textual Justice. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 313–338. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-86.3.313

Tsing, A. L. (2012). ON NONSCALABILITY: The living world is not amenable to precision-nested scales. Common Knowledge, 18(3), 505–524. https://doi.org/10.1215/0961754X-1630424